It could be the plot of an Indiana Jones film – a hidden chamber, a mysterious female pharaoh and a secret room filled with gold. Instead, it is the latest twist in a centuries-old tale; a new theory that inside the famous tomb of Tutankhamun is the hidden entrance to the burial chamber of one of Egypt’s most famous rulers, Queen Nefertiti. Now, for the first time, the evidence that has led archaeologists to this conclusion has been laid out in a new documentary.

The idea first gripped the attention of the world in autumn last year, when radar images bore out archaeologist Nicholas Reeves’ claim that Tutankhamun’s tomb had two undiscovered doors. Chris Naunton, director of the Egypt Exploration Society, who took part in the documentary, says the news was explosive. “It’s the biggest archaeological news from Egypt – or anywhere – for at least a decade.” In fact, he says, he believes that given the interest and the credibility of the theory, it is almost inevitable that the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities will actually agree to explore the idea – by making a small hole in a wall and passing a fibreoptic cable through to find out if there really are concealed rooms. “We are at the point where we have to know. I wouldn’t want to be the person who tells everyone to go home if this is true.”

But when burial tombs are known to have hidden doors, how could these entrances in the most famous archeological site in the world remain undiscovered – for so long?

“This period and the valley of the kings has been raked over by more eyes and brains than any other part of Egyptian history,” Naunton admits. “But Reeves is still finding new ideas against all odds.” This is because the amount of objects in Tutankhamun’s tomb is so overwhelming: “There is so much to go through,” he explains, “that not all the objects have been scientifically photographed and analysed – not even the coffin and the death mask.”

“Despite the mythology of Egyptology, that it is all about traps and hidden doors – why would anyone think that what look like solid walls aren’t solid walls? People don’t look for hidden rooms in any tombs.”

Reeves believes that behind one door will be the tomb of Nefertiti, the wife of the maverick pharaoh Akhenaten, whose beauty was famously captured in a limestone bust now housed in Berlin. During their reign the royal couple attempted to change the whole religion of Egypt, to the monotheistic worship of a new form of the sun god. The art of the period also underwent a dramatic change. Under the new religion, the pharoah’s family – Nefertiti and her children – assumed huge importance. Nefertiti was unique in other ways. “In one relief she is smiting foreigners with a mace – she has them by the hair. That is usually the pharoah’s prerogative.” While royal wives and pharaohs were often indistinct from the royal figures who came before them, Nefertiti was always presented as an individual – in the distinctive headdress that was unique to her. “There is no question that she has an image and a role that is far more prominent than any other woman ever had,” says Naunton.

Most experts now accept that Nefertiti was a pharaoh in her own right, he says, while Reeves argues that she first ruled in tandem with her husband, and then with Tutankhamun, who was only nine when his father Akhenaten died. This, says Naunton, explains why the pair could be buried in the same tomb.

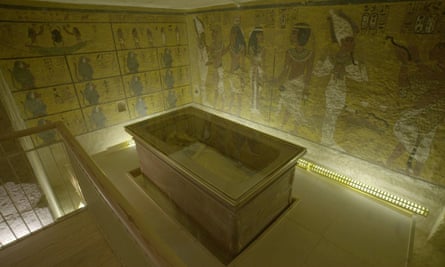

In the documentary, experts explain that Tutankhamun is thought to have been buried in a hurry after his unexpected death at just 19 years old. Pharaohs usually had their tombs, and burial objects, prepared well in advance. Yet Tut’s tomb seemed to be finished in a rush – and to be unusually small for a pharaoh. But if the tomb was originally created for Nefertiti, then a room for her stepson (or son, as some archaeologists believe), hurriedly improvised after his early death, starts to make more sense.

This idea would explain why Tutankhamun’s tomb turns to the right, rather than the left, which is traditional for male tombs. There are also female figures instead of male on some burial objects – which could indicate that these were created for Nefertiti before she became a pharaoh, then discarded when her status rose – before being repurposed for the young boy. Even Tutankhamun’s famous death mask is said to be secondhand, with inscriptions superimposed over older ones that Reeves believes spell out Nefertiti’s name.

Yet Naunton says there is one flaw with this idea: “What’s tricky for me is that it doesn’t look like second-class stuff. We have nothing that looks comparable to this. We have never seen anything better.”

The idea that there are two doorways, Naunton warns, is still just a theory. And even if there do turn out to be doors, many archeologists believe the body of Nefertiti has already been found – DNA tests on another corpse found in the Valley of the Kings has been positively identified by DNA to be Tutankhamun’s mother – which some believe mean it is Nefertiti herself.

Even if the secret rooms turn out not to hold Nefertiti’s tomb, he won’t be dismayed. “If it’s ‘just’ a store room like the others in the tomb, it is probably chock full of unbelievable stuff – the most incredible hoard since Carter found Tut!”

King Tut’s Tomb: The Hidden Chamber is on Friday 19 February at 9pm on Channel 5

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion